Not long ago, buying a router meant choosing between the older Wi-Fi 5 standard and the more recent Wi-Fi 6, with reasonable arguments for choosing either one. But now, those two existing standards are contending with a third option, called Wi-Fi 6E, which the industry has been hyping as Wi-Fi’s biggest upgrade in two decades.

All of which complicates what’s already a fairly agonizing decision, with companies such as TP-Link, Netgear, and Asus selling routers across all three Wi-Fi generations. If you’re trying to expand your wireless coverage or eliminate dead zones, here’s what you need to know:

Why Wi-Fi 5 still matters

The Wi-Fi 5 standard—known as 802.11ac before the industry started branding its standards the same way Apple names its iPhones—launched in 2013, but it remains available today in lower-cost routers. It’s also still a fine option for a couple of reasons:

First, there’s no inherent difference in reception range between Wi-Fi 5 and Wi-Fi 6, so you may be able to get comparable coverage with a much cheaper router.

Amazon’s Eero three-pack with Wi-Fi 5, for instance, costs $169, which is $30 less than the Wi-Fi 6 version with the same advertised 5,000 square feet of coverage. The $200 Google Wi-Fi three-pack and $269 Google Nest Wifi two-pack still use Wi-Fi 5 as well—Google doesn’t even offer Wi-Fi 6 versions—and you can even buy a Wi-Fi 5 mesh system from Vilo for $100. If you’re just trying to extend coverage or eliminate dead zones, buying the best Wi-Fi 5 system you can makes more sense than getting an inferior Wi-Fi 6 system in the same price range.

Vilo

Also, most of your devices probably still use Wi-Fi 5 anyway.

You’ll still find this older standard in the entry-level iPad, nearly all Roku players (except a couple that still use Wi-Fi 4), all Intel-based Macs, all PCs from prior to mid-2019, and all Fire TV devices except the new Fire TV Stick 4K Max. While these Wi-Fi 5 devices will also work with newer Wi-Fi 6 routers, they won’t get any benefits from the newer standard.

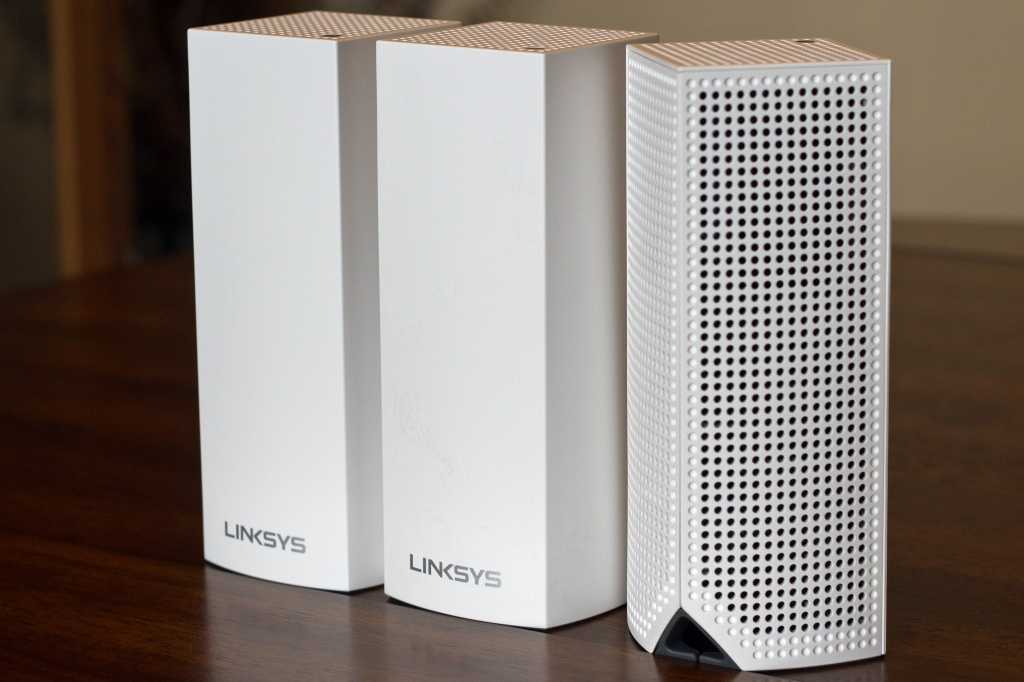

One related note: If you’re buying a mesh router, you might see them advertised as either “dual-band” or “tri-band.” With tri-band systems, the mesh points have their own dedicated line of communication, separate from the ones that feed data to your devices, and that results in less congestion and better speeds. Still, this feature isn’t exclusive to Wi-Fi 6 either. A tri-band Wi-Fi 5 system with more robust backhaul may be a better use of your money than a dual-band system with Wi-Fi 6.

Where Wi-Fi 6 makes sense

Wi-Fi 6 does have some advantages over Wi-Fi 5, but you may be able to get by without them.

If you’re splurging on gigabit internet—even though it’s overkill for most people—you’ll likely want a Wi-Fi 6 router to go with it. As the networking expert Dong Ngo has noted, Wi-Fi 6 can hit speeds of around 1,000 Mbps in the real world with most devices, while Wi-Fi 5 might get to around half those speeds at best.

That extra speed won’t matter for services like Netflix—which consumes around 25 Mbps for 4K video—but could come in handy if you’re downloading torrent files from the internet, moving huge amounts of data between networked storage drives, or streaming from a local media server at extremely high bandwidths.

Wi-Fi 6’s other big advantage is that it can more efficiently handle lots of connections at the same time. One new technology, called OFDMA, is geared toward smart home devices, and may be helpful if you plan to connect a bunch of Wi-Fi-enabled light bulbs and switches to your network. Wi-Fi 6 also extends a feature called MU-MIMO to uploads, which can be useful during simultaneous Zoom calls or online gaming sessions.

Router makers also claim that phones and laptops get better battery life while using Wi-Fi 6, though I’ve yet to see any independent tests that quantify this. They support a stronger from of network security as well, but unless all your devices support Wi-Fi 6, you won’t reap the benefits of that extra protection.

Granted, some Wi-Fi 6 routers benefit from additional features that aren’t directly related to the standard itself, such as better-designed antennas or more powerful processors. (We’ve found, for instance, that TP-Link’s Archer AX50 Wi-Fi 6 router has better performance and range than the Archer A7 with Wi-Fi 5.) Still, Wi-Fi 6 alone doesn’t guarantee better reception, and its speed gains won’t be noticeable for most internet use cases.

Wi-Fi 6E: Still early

Wi-Fi 6E is theoretically a big deal because it adds a new frequency band to home routers for the first time in more than a decade.

Today’s Wi-Fi 5 and Wi-Fi 6 routers offer two bands to minimize congestion, with the 2.4 GHz band offering slower speeds at longer range, and the 5 GHz band offering faster speeds at somewhat shorter range. Your router may automatically divvy up connections between these two bands, or it may display them as separate networks, letting you manually assign devices to each one. (Just to add more confusion, 5 GHz bands are often labeled as “5G” out of the box, despite having nothing to do with your phone’s 5G network.)

Wi-Fi 6E adds a 6 GHz band to the mix, further reducing congestion and allowing for speeds that were seldom possible on the 5 GHz band. But there is one major drawback: Its range is even shorter than that of the 5 GHz band. This will likely improve over time through better hardware and even newer Wi-Fi standards, but for now tests by CNET found no noticeable speed gains for Wi-Fi 6E at close range, and huge drop-offs at further distances.

Meanwhile, current Wi-Fi 6E hardware is expensive—Netgear’s new Wi-Fi 6E mesh system costs $1,500, and even TP-Link’s most basic Wi-Fi 6E router lists for $200, money that would be far better spent on a mesh system with Wi-Fi 5 or Wi-Fi 6.

Netgear

Besides, device support for Wi-Fi 6E is currently limited to Samsung’s Galaxy S21 Ultra and S22 Ultra, a handful of lesser-known phones, and a small number of laptops. (Rumors of Wi-Fi 6E in the iPhone 13 did not pan out.) While other devices will still be able to connect to Wi-Fi 6E routers, they can’t make use of the extra band that’s costing you all that extra money.

None of which means that you should skimp on quality when replacing an old router—I’ve found that old or cut-rate routers tend of be the source of most Wi-Fi problems—but make sure you’re investing in the features that really matter, not the ones that enjoy the most hype.

For more tech advice like this, sign up for my Advisorator newsletter, where a version of this story first appeared.