My desire to power up a laptop with an external graphics card began in 2015, when I set out on a quest to get back into PC gaming—a beloved pastime I’d neglected since childhood.

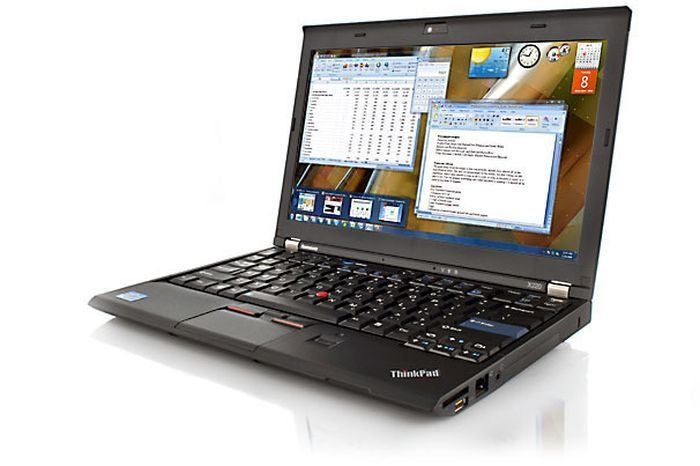

But the only PC I had at the time was a 2011 Lenovo ThinkPad X220 laptop with Intel HD 3000 integrated graphics. That just wouldn’t cut it for proper PC gaming. Sure, the laptop on its own works well enough for older titles like Diablo III, especially on the laptop’s tiny 1366×728-resolution display, but forget about more graphics-intensive modern games on an external 1080p monitor. That’s why I decided to examine external graphics card (eGPU) setups.

And indeed, I found entire communities of people creating DIY setups that connected desktop graphics cards to their laptops via ExpressCard or mPCIe slots to play games on an external monitor. It isn’t hard to configure, and using desktop graphics cards with a laptop has become even easier in recent times. The wide availability of Thunderbolt 3 combined with external graphics card docks has simplified the process even more for people with a modern notebook.

Many do-it-yourself types using Thunderbolt 3, ExpressCard, or mPCIe end up with a plug-and-play experience requiring little to no modification—though it takes some research first. When it’s done, however, you’ll be left with a console-toppling PC gaming setup for about the same price as a new Xbox One S, depending on which graphics card you choose. That’s far cheaper than building a whole new gaming desktop, and you can still take advantage of your laptop’s portability by disconnecting the eGPU hardware.

We’ll walk you through the DIY process for configuring an external graphics card later in this article, along with the sudden rise of streaming PC games from the cloud. First, let’s tackle the modern approach of using a graphics card dock via Thunderbolt 3.

Thunderbolt 3 graphics card docks

Adam Patrick Murray/IDG

Adam Patrick Murray/IDG

A Razer Core connected to a Razer Blade Stealth laptop via Thunderbolt 3/USB-C.

Thunderbolt 3 (TB3) is Intel’s high-speed external input/output connection, capable of speeds up to a blistering 40 gigabytes per second (GBps) over a compatible USB-C port. For resource-intensive activities like gaming, a speedy connection between your laptop and an external graphics card provides a big boost for performance.

Earlier attempts at external graphics card docks existed, but they were usually overpriced and relied on proprietary connection technologies. Thunderbolt 3 levels the playing field, and several companies now offer TB3-based graphics card docks, complete with dedicated power supplies, additional ports, and—of course—room to slot desktop graphics cards.

All is not perfect in the world of Thunderbolt 3-powered graphics, however. Enclosures are, for the most part, still a pricey proposition—much more so than the DIY method we’ll outline later. You’ll also need a relatively new notebook equipped with a Thunderbolt 3-compatible USB-C port. These days most Thunderbolt 3 laptops and graphics card enclosures play nicely together thanks to Intel’s Thunderbolt 3 external graphics compatibility technology, which PC makers must specifically enable.

If you’re in the market for a new laptop compatible with an external graphics card dock, some good choices at this writing include the HP Spectre x360 and the Lenovo Yoga 730. Still, Nando, an eGPU expert who is an administrator at eGPU.io, recommends researching your desired laptop model for compatibility with graphics card enclosures before buying just to be sure.

Once you’ve got your laptop sorted out it’s time to decide which graphics card dock to buy. We can’t cover all possible enclosures here, as virtually every major PC graphics card vendor is rolling out a graphics dock of its own, but we’ll look at some of the major products out there.

Razer Core and Core X

When we looked at the original Razer Core it was the first major TB3 enclosure to make a splash, ostensibly designed for Razer Blade laptops but able to work with any compatible TB3 system. It was also priced at a whopping $500. Since then, the Razer Core has split into two different models: the Core V2 and the Core X.

The Core V2 costs the same $500 as the original. That’s still far more than most other external graphics docks, but this luxurious model sports four USB 3.0 ports for gaming peripherals, a 500-watt internal power supply, and ethernet. It’s also nice to look at with a CNC-machined aluminum exterior and Razer’s Chroma RGB lighting system.

The Core X has a less costly $300 price tag and a 650W power supply, but it lacks USB and ethernet ports. It’s also missing the custom-built finery of the Core V2 since it relies almost entirely on off-the-shelf components. The Core X fits larger cards up to three slots wide. We haven’t reviewed it, but Macworld loved it.

PowerColor Gaming Station

PowerColor

PowerColor

The PowerColor Gaming Station.

PowerColor’s Thunderbolt 3-based Devil Box was a similarly fancy box that sold for $450 in the early days of external graphics docks. It’s still listed on PowerColor’s site, but it isn’t easy to find. PowerColor’s preferred enclosure is the simply named Gaming Station ($300 on NeweggRemove non-product link). The newer box is rocking a 550 watt power supply, ethernet, and five USB 3.0 ports.

PowerColor maintains a list of supported graphics cards and host systems in the specifications section of its Gaming Station webpage. Be sure to check it out before you buy!

Akitio Node

Akitio

AkitioAkitio has gone all-in on external graphics card docks by offering not one but three models: the Node, Node Lite, and Node Pro. A key difference between most of Akitio’s products and the other graphics card enclosures we’ve seen is that, with the exception of the original Node, Akitio’s are not certified by Intel as external graphics (eGFX) peripherals. Instead, they’re general purpose PCIe boxes. We won’t get into the distinction here, but you can read about it on Intel’s Thunderbolt blog.

The original Node packs a 400W power supply and costs $230 on Amazon. It doesn’t offer any extra ports for connecting peripherals, but the enclosure’s lower-priced sibling does. The Node Lite is currently priced around $224 on Amazon. It’s a PCIe-certified box with a DisplayPort port and an extra Thunderbolt 3 port for peripherals, but you’ll need to bring your own power supply as well. Both docks support half-length, full-height, and double-width cards.

Finally, the Akitio Node Pro (currently priced at $330 on Amazon) also has a DisplayPort input and a second Thunderbolt port, a beefier 500W power supply, and a handy retractable lunch box handle if you want to take your graphics dock on the road.

The rest

Gigabyte

GigabyteThose aren’t the only eGPU boxes around. Gigabyte sells the Aorus RTX 2070 Gaming Box, which comes with an Nvidia GeForce RTX 2070 preinstalled for $650 on Amazon, or a version with a GTX 1070 included for $550 on NeweggRemove non-product link. Zotac sells the Amp Box and the Amp Box Mini PCIe enclosures. Heck, even Apple rolled out support for eGFX boxes to MacBook users with macOS 10.13, High Sierra. And for anyone with a compatible Alienware laptop there’s also the Alienware Graphics Amplifier, which uses a proprietary connector but only costs $230 on Amazon.

Asus, HP, Lenovo and many other companies also offer Thunderbolt 3-based graphics card docks. It’s safe to say that external GPUs are a full-fledged trend now—albeit a niche one.

Now, let’s get into transforming older notebooks into gaming machines with our DIY eGPU guide for the Thunderbolt 3 deprived.

The eGPU glossary

Before we get started, we need introduce a few terms. Without a basic vocabulary, the world of eGPUs can get confusing, fast. There’s not much to see here for veteran gamers—you can skip to the next section.

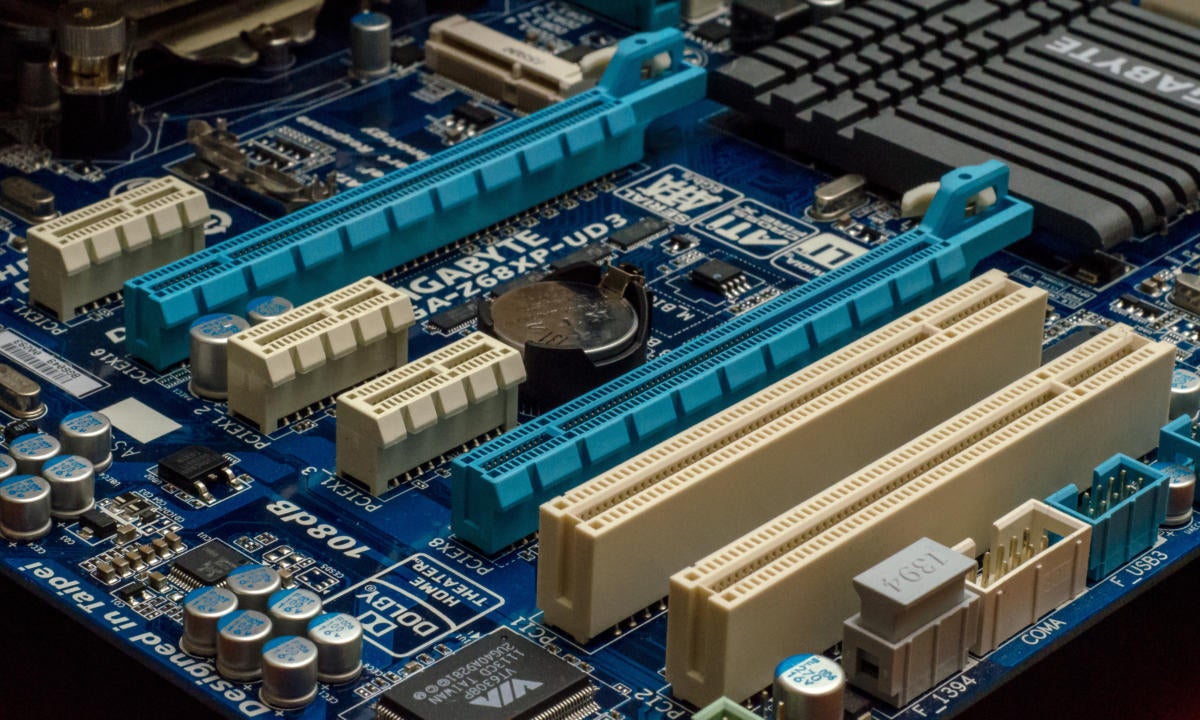

Thomas Ryan/IDG

Thomas Ryan/IDG

PCIe slots in a standard ATX motherboard.

PCIe x16: PCI Express (PCIe) is the motherboard slot that a standard graphics card fits into. The “x16” part means the PCIe slot has 16 lanes that data can travel through. With an eGPU setup we typically compress an x16 slot down to an x1 (1 lane) or x2 (2 lanes) connection to the laptop. That sounds like a raw deal, but it works surprisingly well. PCIe slots come in three generations: 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0. Most new graphics cards will run on PCIe 3.0, which is backward-compatible with version 2.0. PCIe 4.0 is also coming but slowly. AMD announced in January 2019 that its third-generation Ryzen processors would be the first to support version 4, with PCIe 5.0 fast behind it.

PCIe power connector: PCIe can also refer to a type of power connector with six or eight pins.

ATX 24-pin connector: This is another kind of power connector that is commonly used with PC power supplies, and is one of the power options on PCIe adapters.

Thomas Ryan/IDG

Thomas Ryan/IDG

A 24-pin power connector, from a PC power supply.

PCIe adapter/board: This is a small circuit board with a PCIe slot, some HDMI slots, and a whole bunch of power options. The only point of the PCIe adapter is to help the graphics card communicate with the laptop.

Express Card Slot: This is the spot in your laptop that is reserved for wireless broadband cards from a mobile carrier.

mPCIe: This is an interface that some eGPU enthusiasts use to connect their graphics card to their laptop instead of an ExpressCard. It offers a better connection, but it can be a hassle because most mPCIe slots are inside the laptop and inaccessible without cracking open a case.

Thunderbolt: Intel’s blazing fast I/O technology is also an option for an eGPU connection, including DIY set-ups.

BIOS: This is the program that first starts when you boot your computer. It’s usually accessed by hitting F2, another F key, or a special button on your laptop. The BIOS controls a variety of options for your PC including, for example, the boot order.

Frames per second (fps): This is a basic measure of how well a game runs on a given system. The gold standard for PC gamers is 60 fps, though 30 fps is considered playable. Many modern console games still run at 30 fps.

eGPU basic components

A typical eGPU setup requires five basic items: a laptop, a desktop graphics card, an external display, a PCIe adapter/board or enclosure for the card, and a separate power supply for the graphics card (though Thunderbolt 3 enclosures have built-in power supplies). You may also want a laptop cooling pad if you want to play games that go heavy on graphics, like Battlefield V.

Ideally, your laptop packs an Intel or AMD quad-core processor or higher, but a dual-core processor with four threads will also work. A solid-state drive (SSD) can also improve your gaming experience, but it’s not a necessity.The PCIe board is a specialized piece of equipment. The most popular place to grab a board is BPlus in Taiwan (HWTools.net) with options for ExpressCard, m.2 A, E, and M slots, and mPCIe slots.

HWTools

HWTools

A BPlus PCIe board for external graphics card usage.

The best PCIe board on offer at this writing is BPlus’ PE4C v3.0, which works over mPCIe or ExpressCard connections. It offers a PCIe-3.0 x16 slot, plus a nice stand to support your card. The PCIe board comes as a kit with power connectors and an HDMI-to-ExpressCard cable that allows the graphics card to interface with your laptop. Anyone interested in using an m.2 slot could look at the PE4C v4.1. The downside is that the latter supports only PCIe 2.0, while the former supports PCIe 3.0.

Do your hardware research!

Not all DIY eGPU experiences are created equal, but they all have one thing in common: You have to do a bit of research before you get to the plug-and-play part. In fact, you may discover that your particular laptop is not plug-and-play-ready whatsoever, requiring some software tweaks to function properly.

The first thing you should do is read about the experiences other external graphics users have had with your laptop model. You’ll find a ton of eGPU users out there, and unless your model is particularly new or obscure, chances are high that someone has already created an eGPU setup with your laptop model.

If you don’t find anyone with your model, go back a generation, or search for laptops from the same manufacturer to get a sense of the difficulties.

Robert Cardin/IDG

Robert Cardin/IDG

Before I bought eGPU supplies for my 2011 Lenovo Thinkpad X220, I had to research exactly what I’d need.

Several sites can help with DIY eGPU research. The first is eGPU.io, which is solely dedicated to the art of external graphics card configurations and an excellent resource—it even has an eGPU enthusiast Ultrabook buying guide. Other resources include the TechInferno and NotebookReview eGPU threads. Reddit also has an active eGPU community.

One of the most common roadblocks people run across is what’s known as “error 12.” This happens when your Windows system decides it doesn’t have enough resources to run the graphics card. Error 12 can usually be fixed with solutions such as Setup 1.35, a paid software utility by Nando, one of the administrators of eGPU.io.

For more references also check out YouTube, which is full of people running benchmarks or shooting video of their eGPU setups.

Choosing your graphics card

Once you’ve figured out what kind of eGPU experience you’re likely to have, it’s time to start shopping for a graphics card.

I wouldn’t advise going for a top-of-the-line card like the $1,200+ GeForce RTX 2080 Ti. Instead, I’d advise you to keep your graphics card budget around $200 to $300 or less.

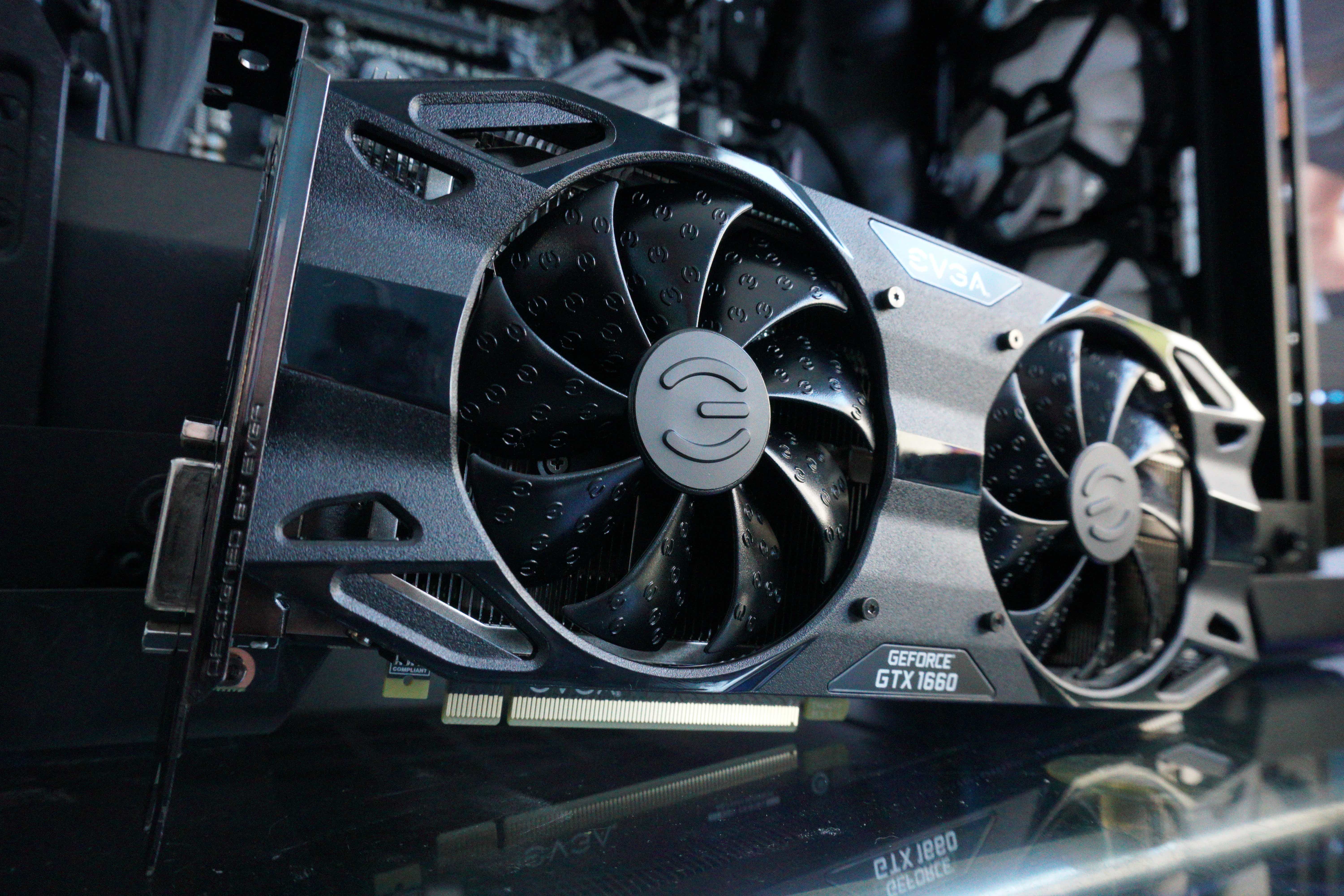

You can get a really great “sweet spot” card for under $300 that should provide at least a few years of future-proofing, such as the $200-ish Radeon RX 580, the $220 GeForce GTX 1660, or the $280+ GeForce GTX 1660 Ti. All are great cards for 1080p gaming with few compromises. If you want to go even lower in price then check out the Radeon RX 570. You can get this card for about $150 (or $130 on sale) and it provides good 1080p gaming performance at Medium to High graphics settings.

As eGPU.io’s Nando told me (via email) when this article was first published, you’ll likely see better performance with a higher-grade card, but it’ll be bottlenecked by that PCIe x1 or x2 connection to your laptop.

If, however, you plan on buying a new desktop sometime soon, then investing in a high-end card right now can be a way to spread out the cost of a new PC over time.

Brad Chacos/IDG

Brad Chacos/IDG

Sapphire’s affordable Radeon RX 580 Pulse graphics card.

More importantly, there’s no guarantee that an eGPU set-up will work until you actually try it. If you’ve done the proper research for your particular laptop model, the chances of a bad experience are fairly low. Nevertheless, there are always outliers, and you just might be the not-so-lucky one who runs into difficulties.

The other decision is whether to go with an AMD or Nvidia card. At the time I put my set-up together most eGPU users tended to go with Nvidia, so that’s what I did. Since then, however, I upgraded to an AMD Radeon card due to the incredible value you can get compared to Nvidia cards that are typically more expensive for equivalent performance.

One thing to keep in mind is that your graphics card needs its own power connector to work in an eGPU setup. That could be a problem for cards with minimal power requirements like the GeForce GTX 1050, which draws its power from the motherboard.

Brad Chacos/IDG

Brad Chacos/IDG

The lack of supplemental power connectors on energy-efficient cards like this MSI GTX 1050 can actually complicate eGPU setups.

If you like the looks of a card like the RX 560 or the GeForce GTX 1050 I’d advise looking for a similarly overclocked card that comes with a power connector. The Radeon RX 570 is a far better performer for a similar street price to the GTX 1050, though.

For more graphics card buying advice check out our regularly updated roundup of the best graphics cards for PC gaming.

Picking your power supply

Along with your graphics card, you’ll also need a power supply unit (PSU) in a DIY eGPU build. There are many reputable brands of PSUs out there, including EVGA, Cooler Master, Corsair, and Seasonic.

Alternatively, you may only need a power brick similar to what powers your laptop. Take Nvidia’s GTX 1050 Ti graphics card, which requires 75 watts of power, according to Nvidia’s specs. Nando advises that your PSU needs about 15 percent more power than what the card (not the system) requires, meaning a 75-watt card will need at least a 90-watt power supply.

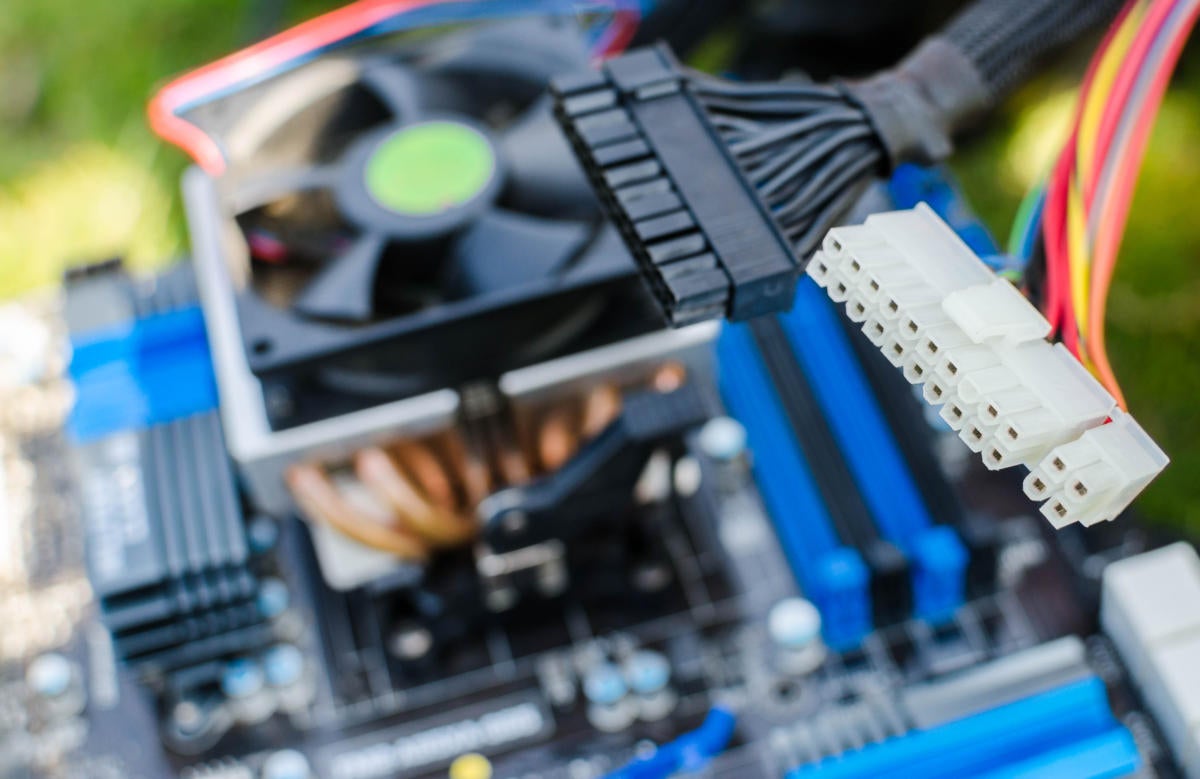

Thomas Ryan/IDG

Thomas Ryan/IDG

A PC power supply.

BPlus recommends that anyone with a graphics card requiring more than 220W should use the ATX power option with a standard PC PSU.

Personally, I just went with a semi-modular Corsair power supply because a standard PSU is so easy to find. PCWorld’s guide to picking a PC power supply can help you make smart buying decisions.

Setting up your eGPU

The research is done, the BPlus board has arrived, your graphics card is ready for unboxing, and so is the PSU. It’s time to get this eGPU rocking.

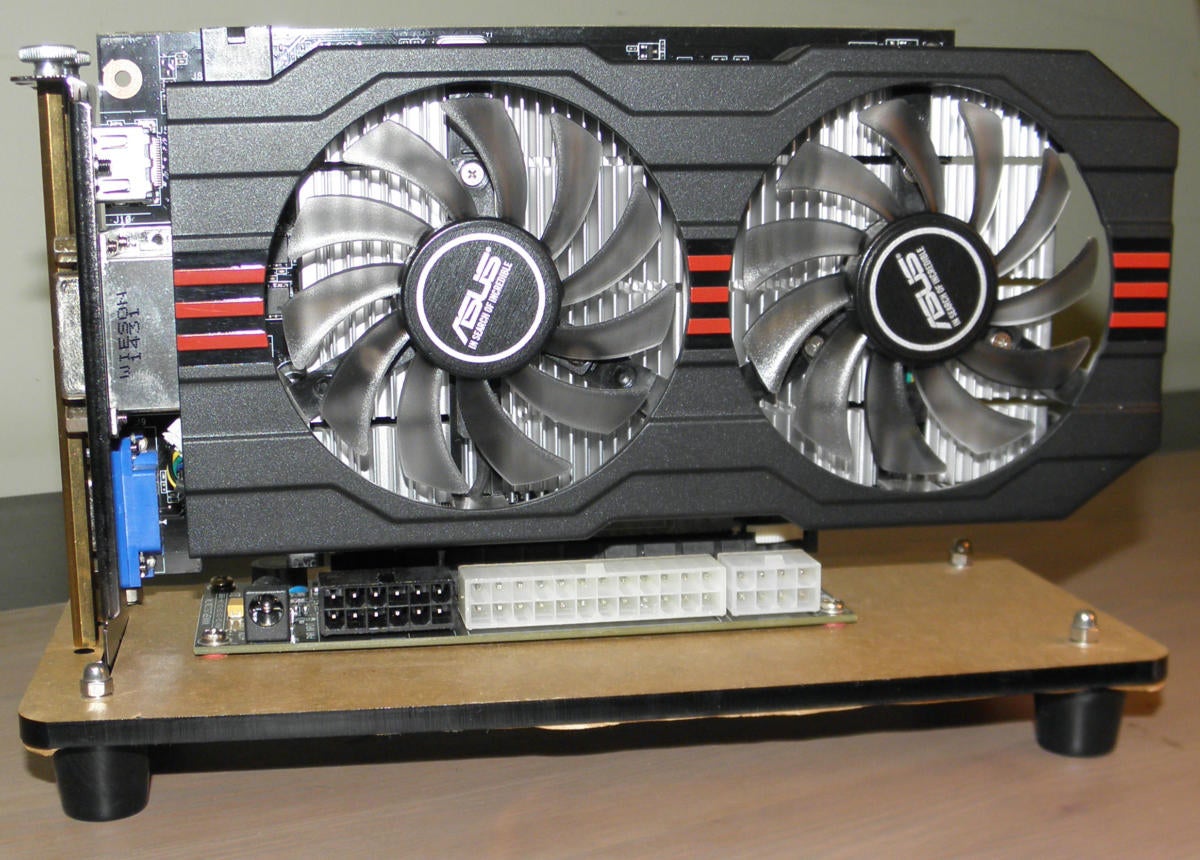

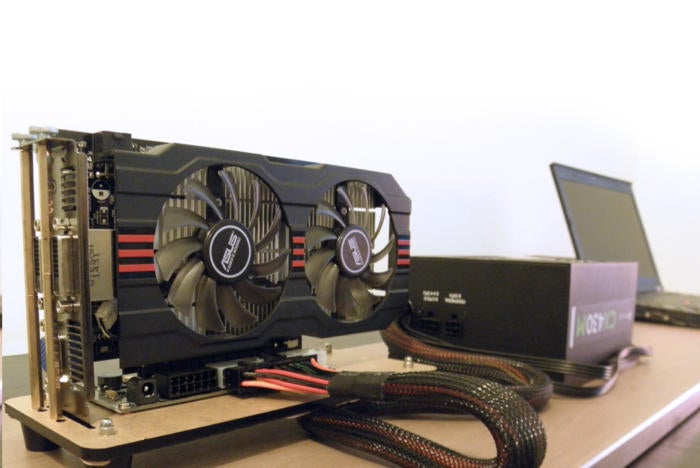

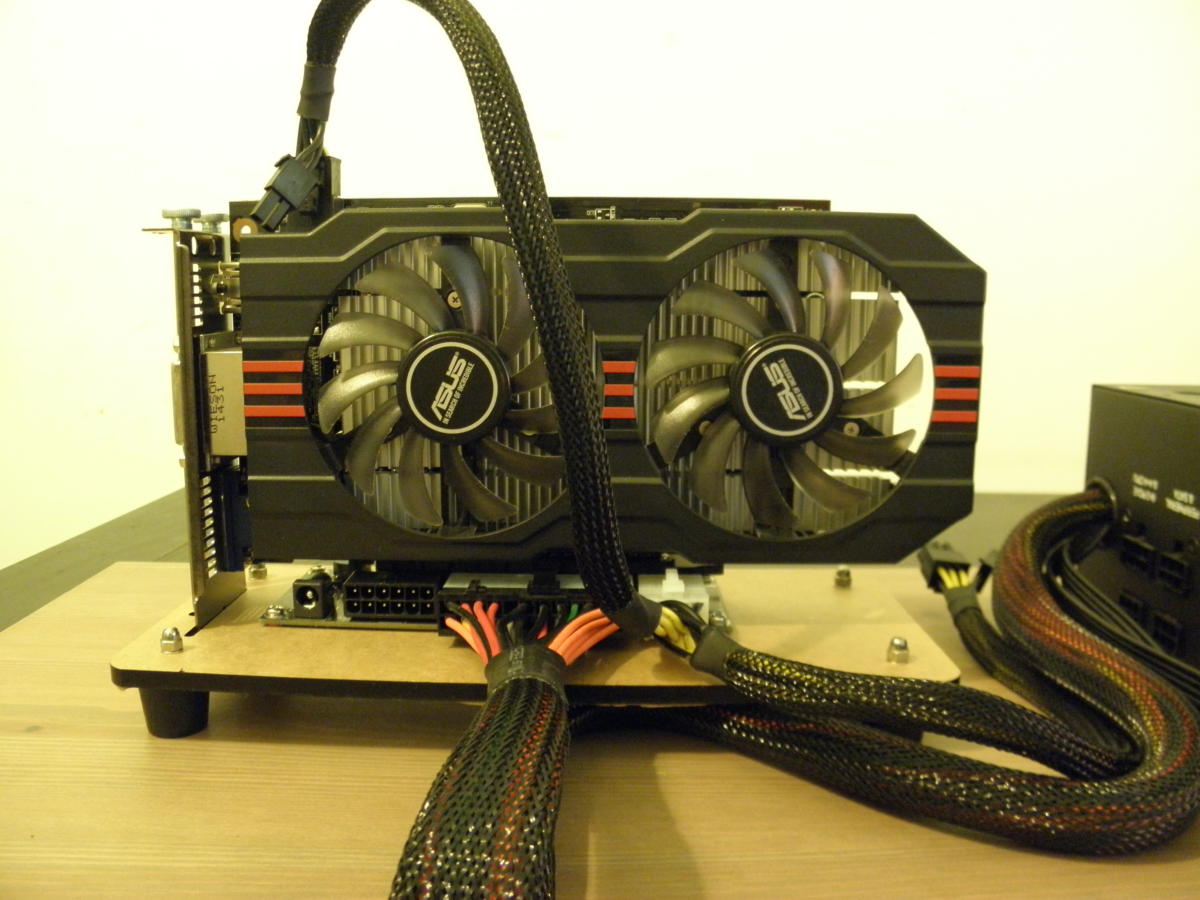

For our example, we hooked up an MSI Armor RX 580 8GB overclocked edition and a Corsair CX430M PSU to a PE4C 2.1a from BPlus. The board connects to an aging Lenovo X220 via an ExpressCard slot, and the card also connects to an external 22-inch 1080p display via one of the RX 580’s DVI ports. The images below show the Asus GeForce GTX 750 Ti that we originally used for this article, but the process is the same regardless of which graphics card you use.

First, slip your graphics card into the PCIe slot on the BPlus board.

Ian Paul/IDG

Ian Paul/IDGNext, hook your (not yet powered-on) PSU’s 24-pin ATX power supply pins into the BPlus board.

Ian Paul/IDG

Ian Paul/IDGNow connect the 8-pin PCIe connector on the board to the 6-pin power connector on the graphics card.

Ian Paul/IDG

Ian Paul/IDGFinally, insert the ExpressCard cable into the laptop, then slide the opposite side of the cable—the one with the HDMI connection—into the HDMI port labled “X1” on the PCIe adapter. At this point you’d also connect your graphics card directly to your external monitor, typically via HDMI or DVI.

Now it’s time for the moment of truth. Flip on your PSU (don’t worry if nothing happens yet), power on the external display, and then boot your laptop—or at least, that’s the boot order that works for me. Some users report that booting an eGPU setup works only when they hook into the ExpressCard slot after the initial boot, or after Windows loads.

Ian Paul/IDG

Ian Paul/IDG

It ain’t pretty, but it works.

Whatever your boot order is, and assuming you had a plug-and-play setup like I did, you should boot into Windows as usual. Your laptop may make a few false starts before it powers on correctly, because you’ve added new hardware to it. Once you’re in Windows, you can check to see if your graphics card is detected by opening the device manager and looking under Display adapters.

If your graphics card is unidentified, manually download and install your card’s drivers from AMD or Nvidia. You may then need to reboot the system to get your eGPU setup working properly.

Once that’s done it’s on to the wonderful world of gaming. Here’s a look at some eGPU benchmarks I ran on my own Radeon RX 580-powered setup to give you a sense of what to expect from a comparable system. Remember that the RX 580 is a 1080p gaming card. Higher powered graphics cards can obviously perform much better.

DIY eGPU benchmarks

Our test rig in this case is the aforementioned Lenovo ThinkPad X220, packing a 2.7GHz dual-core Intel “Sandy Bridge” Core i7 2620-M with HyperThreading and a boost clock of 3.4GHz, 8GB of RAM, a 500GB Samsung 850 EVO SSD, an external 22-inch 1080p display from LG, and Windows 10 Pro 64-bit.

The eGPU hardware consists of an MSI Armor Radeon RX 580 8GB OC, a Corsair CX430M PSU (this PSU is no longer available but a 450W version is), and a BPlus PE4c 2.1a PCIe adapter over HDMI to ExpressCard. This adapter is no longer available on the HWTools website (though this close relation is). This is my second eGPU card. Originally I used the Nvidia GeForce GTX 750 Ti, but recently upgraded. Total cost at the time of writing: About $300, though you can often catch the Radeon graphics card on sale for about $180. Either way it’s still far less than the cost of a whole new gaming PC.

These benchmarks include a look at the difference between the CPU’s integrated graphics (admittedly ancient at this point), the original benchmarks from the 750 Ti when this article was first published, and the more recent results of the RX 580. These tests are not meant to be representative of the GTX 750 Ti’s or the RX 580’s performance. Instead it’s about what someone with a similar eGPU setup can expect—and to drive home that a graphics card offers a huge leap in gaming performance over CPU-integrated graphics even with this eGPU’s significant bottleneck.

My tests used a PCIe 3.0 graphics card over a PCIe 2.0 connection. Results would likely be higher with the BPlus PE4C 3.0 not only because of the newer PCIe slot, but also because the HDMI-ExpressCard cable that comes with that kit supplies a better signal to the laptop.

That’s enough setting of the scene. Let’s dig in.

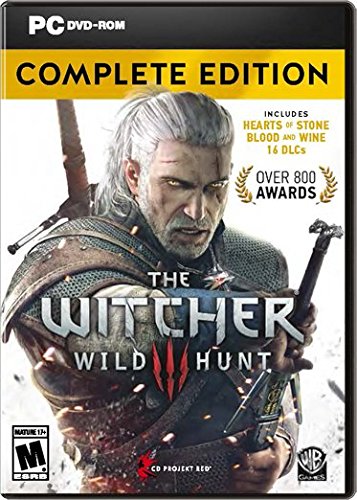

Brad Chacos/IDG

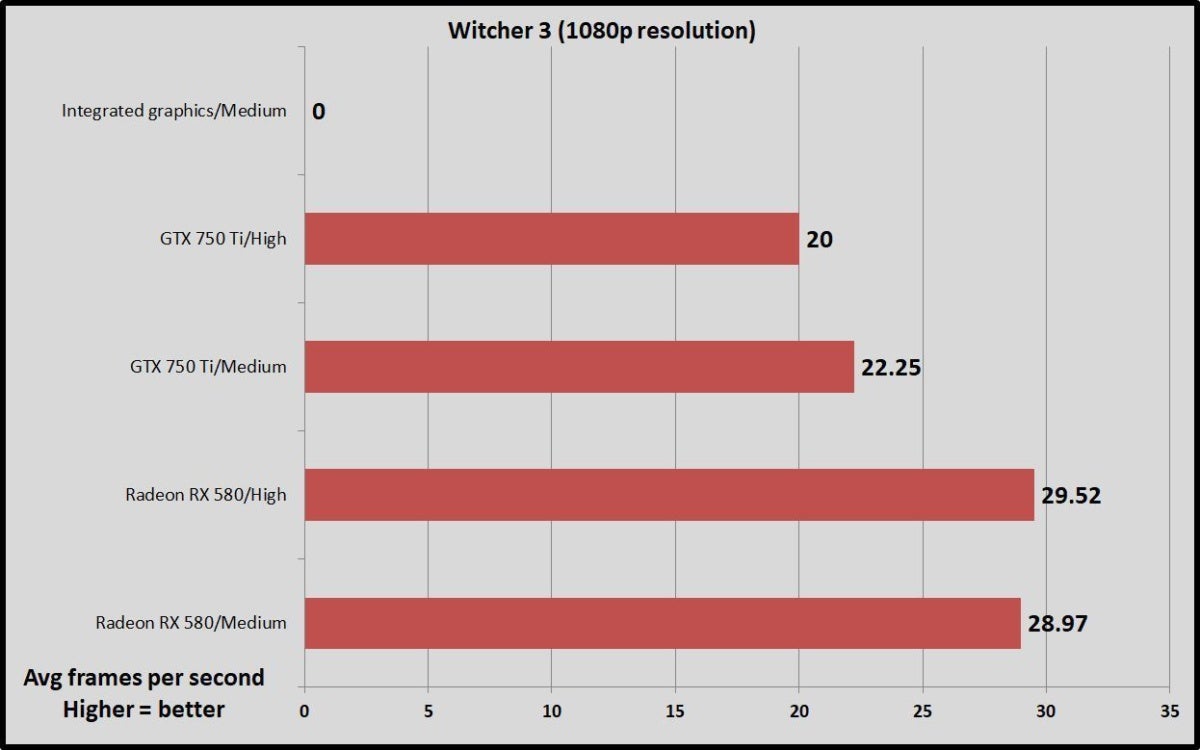

Brad Chacos/IDGAfter looking at my numbers for Witcher 3: The Wild Hunt most hardcore gamers will cringe in horror. With the 750 Ti I had to dial it down to medium graphics at 720p resolution to get to a consistent 30 fps or more and hit console-level quality—and that was with Nvidia Hairworks turned off. Witcher 3 is very graphics-intensive, but I noticed serious stuttering and other problems only when the frame rate went below 22 fps.

Notice that the RX 580 had a small jump in performance over the 750 Ti. It would definitely be noticeable as the newer card came closer to hitting a consistent 30fps during gameplay, but it wasn’t a dramatic shift. That suggests the PCIe bottleneck is quite a limiting factor, even when playing older games with newer cards.

The fact that I can play the game at all, and in full-screen, is a huge step forward over integrated graphics, which couldn’t run Witcher 3 whatsoever. A more powerful graphics card would offer higher frame rates, but it would still be significantly hampered by the bottleneck.

Brad Chacos/IDG

Brad Chacos/IDG Ian Paul/IDG

Ian Paul/IDG Ian Paul/IDG

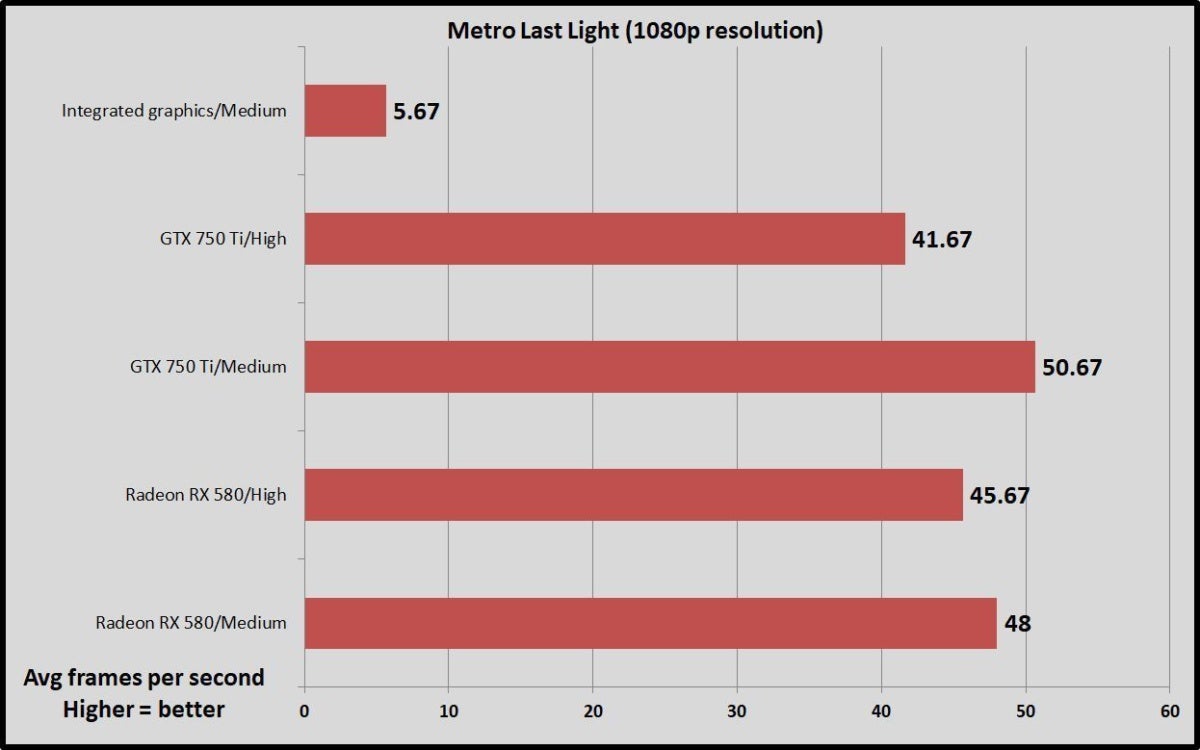

Ian Paul/IDGLess intensive games easily clear the 30fps mark, including Metro: Last Light Redux. To put the integrated graphics performance in proper perspective I’ve also included some screenshots of the benchmark running with the eGPU disconnected. All those backpacks floating in midair are supposed to be attached to soldiers, but the integrated graphics simply can’t handle them.

Taking a look at the results of the GTX 750 Ti and the RX 580 it’s odd that the 750 Ti squeaked out an extra two frames and change per second on the medium settings over the newer AMD card. That was unexpected—though the benchmark ran three times in a row. The high settings, meanwhile, show a slight bump the other way around. Again, we’re seeing the bottleneck at work, though this game has always performed better on Nvidia hardware.

In fact, because of that PCIe bottleneck not all games run flawlessly on this eGPU setup. I tried Battlefield 4 way back when this article was first published, and the game ran for only 10 minutes before it failed. Star Wars Battlefront II was also a bust, as was Madden NFL 19. Maybe EA just doesn’t like eGPU set-ups, but it’s a reminder that you need to buy your games from online retailers with return policies like GOG and Steam, or those that offer limited-time trials like EA’s Origin Access. You don’t want to be stuck paying $60 for a game that won’t work on your system.

Brad Chacos/IDG

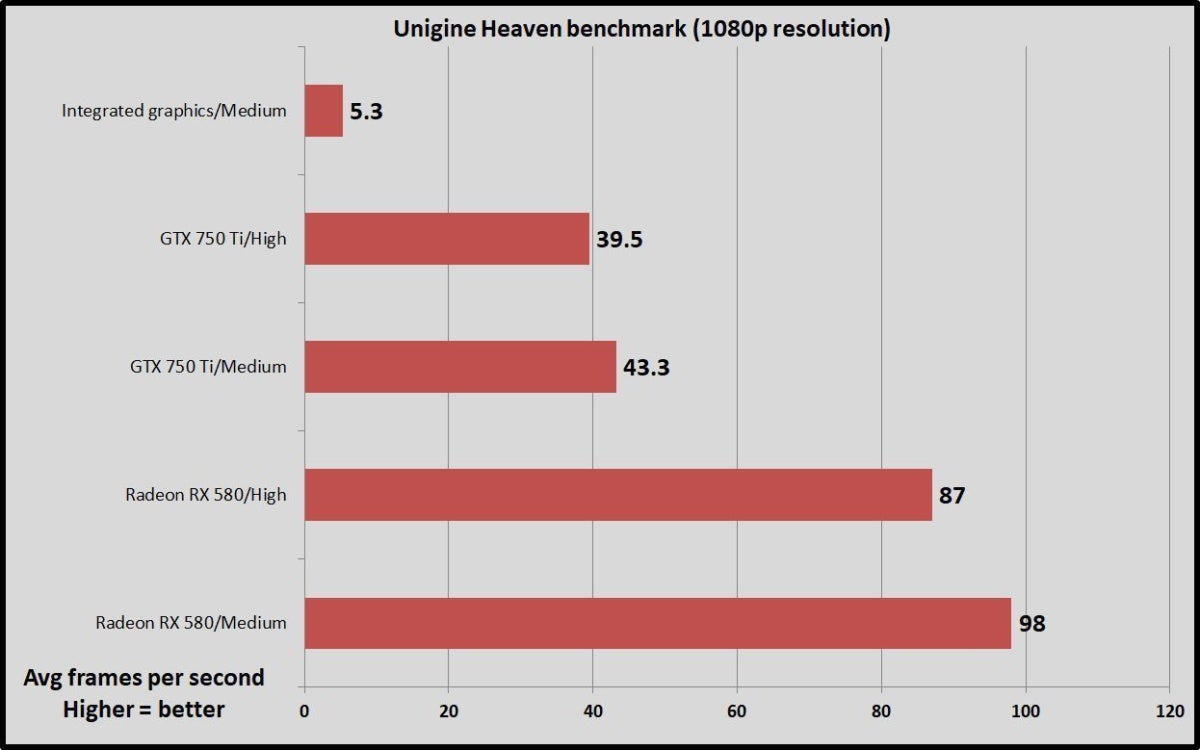

Brad Chacos/IDGFinally, check out the major frame rate leap that my eGPU brings in the Unigine Heaven 4.0 benchmark. This is where the RX 580 showed its true prowess over the 750 Ti completely blowing away the older GTX model.

Gaming from the cloud

If an eGPU set-up isn’t in the cards there’s another option. Several services are currently working on bringing cloud-based game streaming to the masses.

With cloud gaming, all you need is a basic Windows PC or a MacBook to run the client software, while a more robust PC runs the actual game in the cloud. Both of the above mentioned services use the same basic format. You buy your own PC games from Steam or a similar service, then install it on your cloud-based virtual gaming machine and stream the gameplay to your physical laptop.

Nvidia

Nvidia

GeForce Now and other cloud services let you game even if your laptop can’t game.

One is Nvidia’s GeForce Now, currently in a closed beta and provided at no cost for accepted testers. Nvidia hasn’t commented on current pricing plans, but when GeForce Now was first introduced the service was expected to charge $25 for 20 hours on a virtual PC with the capabilities of a GTX 1060 graphics card, or 10 hours on a GTX 1080-equivalent virtual PC. Those cards will likely change once/if GeForce Now rolls out to the wider public.

Twenty hours sounds like a good chunk of game time, but when you consider that a large game like The Witcher 3 takes 60-100 hours to complete, and you need to buy your own copy of the game to play it, Nvidia’s service doesn’t sound especially budget-friendly—if pricing remains the same at launch. GeForce Now may be more compelling as a “backup” option—letting you play your games on your work laptop while you’re on the road, for example.

Now for the good news: GeForce Now is currently free-as-in-beer-free during the beta period for the PC, Mac, and Nvidia Shield TV. PC and Mac users need to sign-up and request access, but Shield TV owners can get automatic access to the beta as of July 2018. We tested GeForce Now’s performance in 2018 over a 25Gbps home connection and were suitably impressed with its performance.

Things get murkier beyond GeForce Now.

LiquidSky was another early cloud streaming competitor, but it’s since gone into hiatus after a beta that started pricing at $15 per month for 25 hours of 1080p gameplay and 200GB of gaming storage. French company Blade recently expanded to the U.S. in limited fashion but its “Shadow” streaming service offers a somewhat bumpy ride for its $30 per month asking price. Other companies such as China-based Tencent recently announced something called Instant Play, and Poland-based Vortex currently offers streaming for select games.

More established tech goliaths appear poised to take on cloud-based streaming, in the form of Google’s nebulous, yet ambitious Stadia and Microsoft’s Xbox-centric Project xCloud. Sony’s been into game streaming ever since it gobbled up what was left of Gaikai, an early pioneer in the space, and PlayStation Now has evolved into the surprise OnLive replacement you didn’t know you wanted—though it’s (obviously) limited to PlayStation titles.

Cloud gaming is a solid, if sometimes pricey, concept that may very well be the best way to play games in the future if the price is right. For now, however, the thriftier way to get gaming is to try a DIY eGPU set-up—especially if buying a full gaming desktop isn’t in the cards.